Fluoroquinolone Delirium Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps assess the risk of delirium in older adults starting fluoroquinolone antibiotics based on key risk factors.

Patient Information

Medication Factors

Key Takeaways

- Fluoroquinolones can trigger delirium in patients over 65, often within the first three days of therapy.

- Mechanisms involve GABA‑A receptor inhibition and possible NMDA‑receptor activation.

- Risk spikes with renal impairment, high doses, and pre‑existing brain disease.

- Prompt drug discontinuation usually reverses symptoms within 48‑96 hours.

- Alternative antibiotics and dose adjustments are recommended for high‑risk older adults.

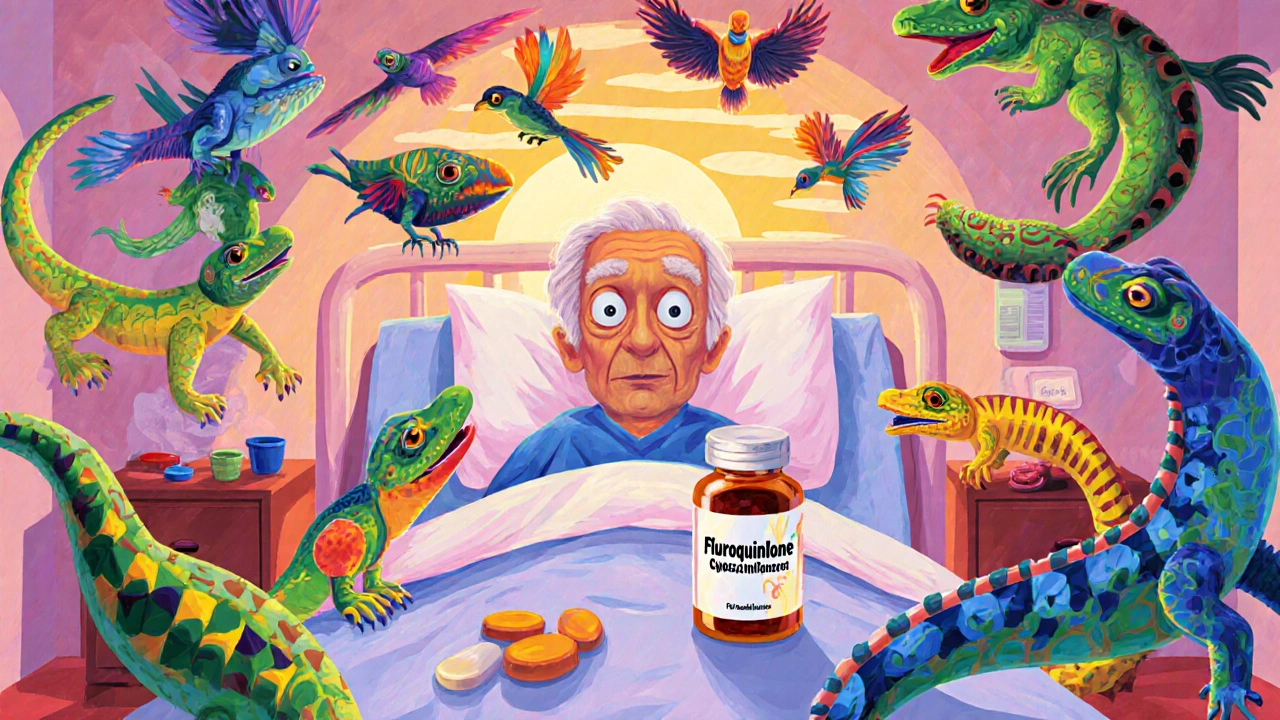

When prescribing antibiotics, Fluoroquinolones are a class of broad‑spectrum agents that inhibit bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, making them effective against many Gram‑negative and some Gram‑positive pathogens. They’re popular for urinary‑tract infections, community‑acquired pneumonia, and a handful of other common infections. But for older adults, the story isn’t just about bacterial kill - the drugs can also mess with the brain.

Delirium is an acute, fluctuating disturbance of attention, awareness, and cognition, often triggered by illness, medication, or metabolic derangements. In patients over 65, delirium isn’t just uncomfortable; it dramatically raises the odds of a longer hospital stay, institutionalisation, and even death. Recognising that fluoroquinolones are a hidden driver of this syndrome is essential for clinicians, caregivers, and anyone involved in medication decisions for seniors.

Why Fluoroquinolones Affect the Brain

The neuro‑toxic profile of fluoroquinolones stems from two main mechanisms:

- GABA‑A receptor inhibition - these drugs block the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, tipping the excitatory‑inhibitory balance toward hyper‑excitability.

- Potential activation of NMDA receptors, which can cause excitotoxic damage when over‑stimulated.

Both pathways can precipitate confusion, visual or auditory hallucinations, and disorientation - the classic hallmarks of delirium. The effect is dose‑dependent, with higher plasma concentrations (often seen in renal impairment) correlating with more pronounced symptoms.

Who’s at Greatest Risk?

Not every senior who receives a fluoroquinolone will develop delirium, but certain factors dramatically raise the odds:

- Age > 65 years - age‑related blood‑brain barrier permeability increases drug entry into the CNS.

- Renal insufficiency - up to 85 % of levofloxacin is cleared renally; reduced clearance leads to higher brain levels.

- Pre‑existing cognitive disease - dementia, Parkinson’s, or prior strokes lower the brain’s reserve.

- High daily doses - e.g., 750 mg levofloxacin per day has been linked to rapid symptom onset.

- Concurrent CNS‑active drugs - benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, or opioids can have additive effects.

Clinical data from the SHM Abstracts show that roughly 40 % of hospitalized adults over 65 receive a fluoroquinolone at some point during their stay, making vigilance crucial.

Typical Presentation Timeline

Delirium usually emerges within 1‑3 days after the first dose. The Kucukarslan et al. case report (2018) documented a 78‑year‑old who became disoriented and began hearing voices on day 3 of levofloxacin therapy; symptoms vanished 48 hours after the drug was stopped.

Key clinical clues include:

- Sudden disorientation to time, place, or person.

- Visual or acoustic hallucinations.

- Rapidly worsening attention span.

- Irritability or agitation without a clear infectious cause.

- Memory gaps that resolve after drug withdrawal.

Because other causes (electrolyte imbalance, infection, stroke) can mimic these signs, a systematic work‑up is essential.

Diagnosing Fluoroquinolone‑Induced Delirium

The DSM‑IV (and DSM‑5) criteria for delirium still apply: acute onset, fluctuating course, inattention, plus either disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness. In practice, the diagnosis hinges on a high index of suspicion and exclusion of alternatives.

A practical diagnostic flow might look like this:

- Confirm recent fluoroquinolone exposure (within past 72 hours).

- Rule out metabolic derangements: check electrolytes, glucose, renal function.

- Obtain a non‑contrast brain CT or MRI if focal deficits are present.

- Review concurrent medications for other neurotoxic agents.

- If no other cause emerges, attribute delirium to the fluoroquinolone and discontinue the drug.

Laboratory and imaging studies are often normal, as demonstrated in the Kucukarslan case where electrolytes, CT, and EEG were all unremarkable.

Management and Recovery

The cornerstone of treatment is immediate drug cessation. Substituting a non‑neurotoxic antibiotic-often a beta‑lactam such as amoxicillin‑clavulanate for urinary infections or a macrolide for atypical pneumonia-usually clears the picture.

Supportive care includes:

- Re‑orientation cues (clocks, calendars, familiar objects).

- Hydration and nutrition.

- Sleep‑promotion strategies (dim lights, noise reduction).

- Avoidance of restraints and unnecessary sedatives.

Most patients experience full resolution within 48‑96 hours, but the window can stretch to a week in those with severe renal dysfunction.

Prevention Strategies for Clinicians

Given the predictable risk profile, prevention is often more effective than treatment. Here’s a quick checklist:

- Screen every patient > 65 years for renal function (eGFR) before prescribing.

- Prefer alternative agents when possible, especially for uncomplicated urinary‑tract infections.

- If a fluoroquinolone is unavoidable, adjust the dose according to CrCl and monitor closely for the first 72 hours.

- Document the risk discussion in the medical record-this satisfies the FDA’s 2018 safety communication requirement.

- Educate nursing staff and caregivers to flag sudden confusion early.

Many health systems now embed Clinical Decision Support (CDS) alerts that pop up when a prescriber orders a fluoroquinolone for a patient with eGFR < 50 mL/min or documented dementia.

Comparing Antibiotic Options: Delirium Risk Profile

| Antibiotic Class | Typical CNS Penetration | Delirium Risk (Relative) | Common Indications in Older Adults |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolones (e.g., levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin) | 50‑90 % of plasma levels | High | UTI, CAP, prostatitis |

| Beta‑lactams (e.g., amoxicillin‑clavulanate) | 10‑20 % of plasma levels | Low | Sinusitis, otitis media, uncomplicated UTI |

| Cephalosporins (e.g., cefepime) | 30‑40 % (dose‑dependent) | Moderate (neurotoxicity via GABA antagonism) | Severe sepsis, hospital‑acquired pneumonia |

| Macrolides (e.g., azithromycin) | 5‑15 % of plasma levels | Low | Atypical pneumonia, COPD exacerbation |

The table makes it clear why many geriatric formularies now flag fluoroquinolones as “high‑risk” for delirium and prefer beta‑lactams or macrolides when clinically appropriate.

Regulatory Landscape and Guideline Updates

In July 2018, the FDA issued a safety communication (announcement 2018‑11128) that added explicit warnings about attention disturbances, memory impairment, and delirium to every systemic fluoroquinolone label. The agency also recommended reserving these drugs for infections where no safer alternatives exist.

The American Geriatrics Society incorporated fluoroquinolones into its 2023 Beers Criteria as “potentially inappropriate medications” for older adults, citing delirium risk as a primary concern.

Since the warnings, prescribing trends have shifted. A 2020 JAMA Network Open analysis showed a 20.4 % drop in fluoroquinolone use for adults over 65, and UCSF’s antimicrobial stewardship program reported a 35 % reduction in levofloxacin prescriptions for uncomplicated UTIs after implementing a delirium‑risk protocol.

Real‑World Stories: Clinician Perspectives

On the Student Doctor Network, a resident shared: “I treated an 82‑year‑old with levofloxacin for pyelonephritis. By day 2 she was shouting at invisible people. We stopped the drug, switched to ceftriaxone, and she was back to herself in two days. The lesson? Never assume the infection is the only cause of new confusion.”

Similarly, a Reddit r/medicine post from March 2021 recounted three separate cases where fluoroquinolone‑induced delirium was only recognised after 24‑48 hours of observation, underscoring the need for early vigilance.

Looking Ahead: Research and Future Directions

Scientists are exploring biomarkers-such as serum GABA‑A subunit antibodies-that might predict susceptibility before the drug is even given. The FDA’s FAERS database recorded 1,842 neuropsychiatric reports linked to fluoroquinolones from 2015‑2020, prompting ongoing pharmacovigilance.

Pharmaceutical companies are also investigating new quinolone derivatives with reduced CNS penetration, aiming to preserve antimicrobial potency while lowering neuro‑toxic potential.

In practice, the next five years should see fluoroquinolone prescribing for older adults decline by another 15‑25 % as stewardship programs mature and clinicians become more comfortable with alternative agents.

Bottom Line for Practitioners

If you treat patients over 65, ask yourself three questions before hitting “send” on a fluoroquinolone prescription:

- Is there a safer antibiotic that covers the likely pathogen?

- Does the patient have renal impairment or a history of cognitive decline?

- Can I set up monitoring (or an alert) for the first 72 hours?

Answering “no” to any of these should trigger a re‑evaluation of the drug choice. A quick switch can spare a patient weeks of confusion, a longer hospital stay, and a possible transition to long‑term care.

Frequently Asked Questions

How soon after starting a fluoroquinolone can delirium appear?

Symptoms typically emerge within 1‑3 days of the first dose, although rare cases have been reported as early as 12 hours.

Is delirium caused by all fluoroquinolones equally?

Levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin have the most documented cases, likely because they’re the most prescribed. Gemifloxacin and moxifloxacin also carry risk, but data are scarcer.

Can dose reduction prevent delirium?

Reducing dose in renal impairment lowers plasma levels and therefore CNS exposure. However, even a reduced dose can trigger delirium in highly vulnerable patients; avoiding the class altogether is safest when alternatives exist.

What alternative antibiotics are recommended for older adults?

Beta‑lactams (amoxicillin‑clavulanate, cefuroxime), macrolides (azithromycin), and nitrofurantoin for uncomplicated UTIs are generally preferred because they have low CNS penetration and lack GABA‑A antagonism.

Is the delirium always reversible?

In the majority of reported cases, symptoms resolve within 48‑96 hours after stopping the drug. Persistent deficits are rare but can occur if delirium went unrecognized for an extended period.

Staying alert to this side effect not only protects patients’ brains but also reduces healthcare costs linked to prolonged stays and post‑acute care. The next time you consider a fluoroquinolone for an older adult, weigh the infection severity against the clear delirium risk-and choose wisely.