Opioid Dose Calculator for Liver Disease

Patient Assessment

Key Safety Information

Never use morphine in Child-Pugh C or severe MELD scores - high risk of M3G accumulation causing seizures and confusion

Transdermal fentanyl and buprenorphine patches are preferred for advanced liver disease (bypass first-pass metabolism)

Remember: Dose reductions are essential but not sufficient alone - extend dosing intervals and monitor closely for respiratory depression

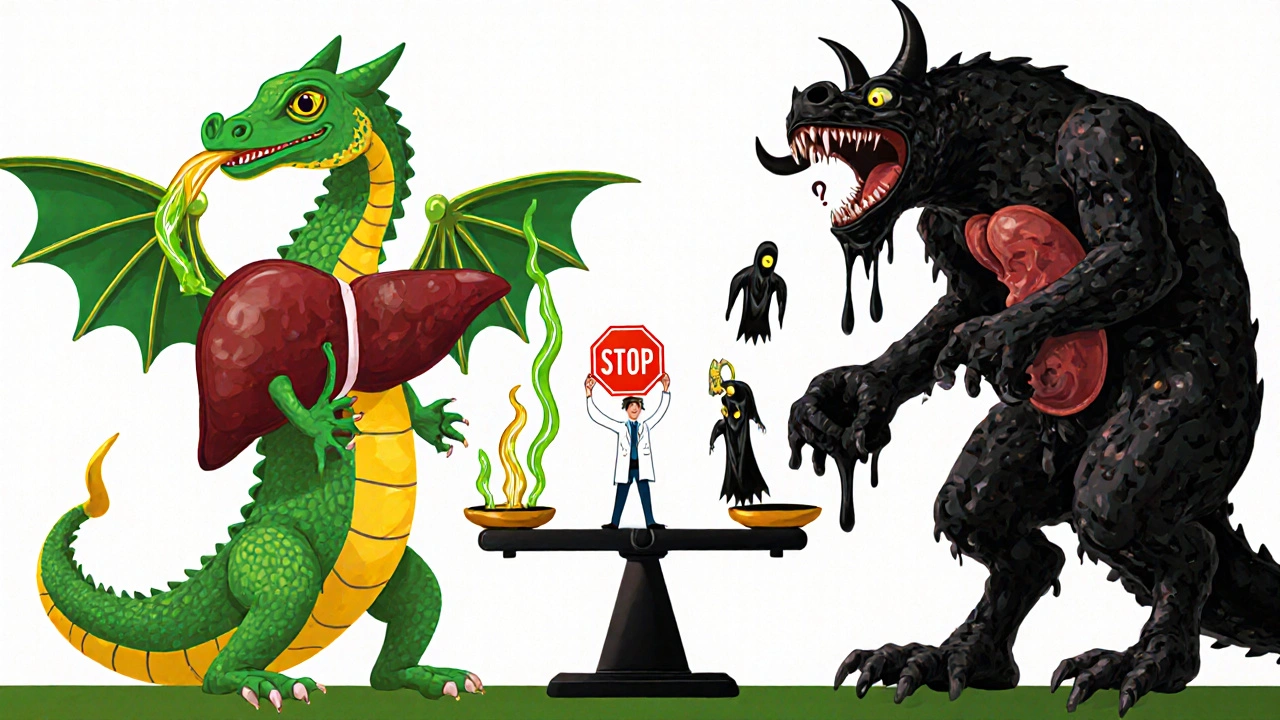

When someone has liver disease, taking opioids isn’t just risky-it’s like driving with a broken brake pedal. The liver doesn’t just process pain meds; it breaks them down, filters out toxins, and keeps the body from getting overwhelmed. But when the liver is damaged, that system fails. Opioids build up. Side effects multiply. And what was meant to ease pain can turn into a silent, dangerous overdose.

How the Liver Normally Handles Opioids

The liver uses two main systems to break down opioids: the cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These are like specialized factories inside liver cells. CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 handle drugs like oxycodone and fentanyl. Glucuronidation, led by UGT enzymes, processes morphine and hydromorphone. These systems turn opioids into water-soluble compounds so the kidneys can flush them out.

Take morphine. About 90% of it gets turned into two metabolites: morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which is even stronger than morphine itself, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which does nothing for pain but can cause seizures and confusion. In a healthy person, M6G and M3G are cleared quickly. But in liver disease, that clearance slows-sometimes dramatically.

What Happens When the Liver Fails

As liver function declines, opioids don’t get broken down. They stick around longer. Their half-life-the time it takes for half the drug to leave your body-spikes. For oxycodone, the normal half-life is about 3.5 hours. In severe liver disease, it can stretch to 14 hours on average, and in some cases, over 24 hours. That means if you take a standard dose, you’re not just feeling pain relief-you’re slowly accumulating a toxic load.

Studies show that people with advanced cirrhosis can have up to a 40% higher peak concentration of oxycodone in their blood. Morphine clearance drops by 50% or more in moderate to severe liver impairment. That’s not a small adjustment. It’s a red flag.

And it’s not just about dose size. Timing matters too. Giving morphine every 4 hours to someone with cirrhosis is like pouring gasoline on a fire. The drug doesn’t clear fast enough. It piles up. That’s why experts say: reduce the dose and extend the interval.

Which Opioids Are Riskiest in Liver Disease?

Not all opioids are created equal when the liver is damaged.

Morphine is one of the worst choices. Because it relies on glucuronidation-something the liver struggles with in disease-it’s a ticking time bomb. Even small doses can lead to M3G buildup, causing agitation, hallucinations, or myoclonus (involuntary muscle jerks). In advanced liver disease, morphine should be avoided if possible.

Oxycodone is metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. In cirrhosis, CYP3A4 activity drops by 30-50%. That means more of the drug stays active. Guidelines recommend starting at 30-50% of the normal dose. Even then, patients need close monitoring for drowsiness, low breathing rate, or confusion.

Methadone is tricky. It’s broken down by multiple enzymes, so it’s less dependent on one pathway. But there’s no solid dosing guide for liver disease. Doctors often use it cautiously in chronic pain patients with cirrhosis, but they watch for QT prolongation and respiratory depression.

Fentanyl and buprenorphine are often better options. They’re metabolized less by the liver and more by the lungs and kidneys. Transdermal patches (like fentanyl patches) bypass first-pass liver metabolism entirely. That makes them safer for people with advanced liver disease-when used correctly.

Hidden Dangers: Gut-Liver Axis and Long-Term Use

Most people don’t realize opioids don’t just hurt the liver-they can make liver disease worse. Chronic opioid use changes the gut microbiome. It kills off good bacteria and lets harmful ones grow. That imbalance triggers inflammation, which travels straight to the liver through the portal vein.

This is called the gut-liver axis. In patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), that inflammation speeds up scarring. Studies now link long-term opioid use to faster progression of fibrosis. It’s not just about overdose. It’s about making the underlying disease worse.

And it’s not just alcoholics or heavy drinkers. People with diabetes or obesity-common causes of NAFLD-also have reduced CYP3A4 activity. That means even if they’ve never touched alcohol, their liver is already struggling to process opioids.

What Doctors Should Do

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule, but there are clear, evidence-based steps:

- Start low, go slow. For oxycodone, begin at 30-50% of the usual dose. For morphine, reduce by at least 50% and extend dosing to every 6-8 hours instead of 4.

- Avoid morphine in advanced disease. Use alternatives like buprenorphine patches or fentanyl patches when possible.

- Monitor closely. Watch for sedation, slow breathing, confusion, or muscle twitching. These aren’t just side effects-they’re warning signs of toxicity.

- Check liver function regularly. Albumin, bilirubin, and INR levels help estimate how well the liver is working. Use Child-Pugh or MELD scores to guide dosing decisions.

- Consider non-opioid options. Acetaminophen (in low doses), gabapentin, or NSAIDs (if kidney function allows) may be safer first-line choices.

There’s no perfect opioid for liver disease. But there are smarter choices. And ignoring the science can be fatal.

What We Still Don’t Know

Even with all we’ve learned, big gaps remain. There’s no clear dosing protocol for tramadol in cirrhosis. We don’t know how oxymorphone behaves in advanced liver failure. Fentanyl’s metabolism in NAFLD isn’t well studied. And while transdermal delivery helps, we don’t yet have data on how long patches remain effective when liver enzymes are low.

Research is also lacking on whether opioids cause direct liver damage-or if the harm comes only from secondary effects like gut dysbiosis and inflammation. If opioids are directly toxic to liver cells, that changes everything.

For now, the safest approach is simple: use the lowest effective dose, choose the safest drug for the patient’s liver condition, and never assume a normal dose is safe.

Final Takeaway

Opioids aren’t inherently bad. But in liver disease, they become unpredictable. What works for a healthy person can kill someone with cirrhosis. The liver doesn’t just process drugs-it protects you from them. When it’s damaged, that protection vanishes.

If you’re managing pain in someone with liver disease, don’t just adjust the dose. Re-think the whole plan. Talk to a pharmacist. Use guidelines. Monitor like your life depends on it-because it might.

Can opioids cause liver damage on their own?

Opioids themselves aren’t directly toxic to liver cells in the way acetaminophen is. But long-term use can worsen existing liver disease by disrupting the gut microbiome, triggering inflammation, and speeding up fibrosis. This indirect damage is especially dangerous in patients with NAFLD or ALD.

Is morphine safe for patients with cirrhosis?

No, morphine is generally not recommended in moderate to severe cirrhosis. It’s metabolized into M3G and M6G, both of which accumulate when the liver can’t clear them. M3G can cause neurological side effects like seizures and confusion. Even reduced doses carry high risk. Avoid morphine in advanced liver disease.

What’s the best opioid for someone with liver disease?

Buprenorphine and fentanyl (especially transdermal patches) are preferred. They’re metabolized by multiple pathways and bypass first-pass liver metabolism when given through the skin. Oxycodone can be used but only at 30-50% of the normal dose with extended intervals. Always avoid morphine and hydromorphone in advanced disease.

How do I know if an opioid is building up in my system?

Watch for signs of toxicity: extreme drowsiness, slow or shallow breathing, confusion, dizziness, muscle twitching, or hallucinations. These aren’t normal side effects-they’re red flags. If you or a loved one is on opioids and has liver disease, check in with your doctor every 1-2 weeks, especially after a dose change.

Can I take acetaminophen instead of opioids if I have liver disease?

Acetaminophen is often safer than opioids for mild to moderate pain in liver disease-but only in low doses. The maximum safe daily dose is 2,000 mg for people with cirrhosis, not the usual 3,000-4,000 mg. Higher doses can cause acute liver failure. Always check with your doctor before using it regularly.

Do age or gender affect how opioids are processed in liver disease?

Age and gender don’t significantly change how opioids are metabolized in liver disease. CYP3A4 activity is slightly higher in women, but not enough to change dosing. The key factor is liver function-not age or sex. A 70-year-old with mild cirrhosis may handle opioids better than a 40-year-old with advanced disease.